By C. Todd Lopez

WASHINGTON (Dec. 04, 2020) -- When COVID-19 flared up earlier this year, the government and military looked for the medical supplies needed to keep citizens and medical personnel safe. The search put a spotlight on a fact the Defense Department had become aware of but not many had talked about: Many goods and supplies critical to the nation are not made in the U.S., but overseas -- and, many times, their manufacture was by nations the U.S. doesn't consider to be allies, said the undersecretary of defense for acquisition and sustainment.

"When the pandemic rolled around and everyone realized how vulnerable we were as a nation without the [personal protective equipment] and the pharmaceuticals that we needed where we depended on offshore sources, that heightened everybody's awareness of how that spreads through the defense industry, as well," Ellen M. Lord said during a discussion with the Hudson Institute that was recorded Dec. 1. "COVID was a type of silver lining for us in a way."

Lord said the department worked in 2017 and 2018 on a study, in response to a presidential executive order, to look at the defense industrial base, or DIB.

"We published a report in 2018," she said. "What that really did was segment the defense industrial base, and it gave us a lexicon to talk about what that industrial base consisted of. We also identified where we had vulnerabilities and fragility in the industrial base -- and a lot of that was where we had 100% dependency offshore, and especially when we were relying on nations who aren't particularly our partners and allies for critical items."

As a result of COVID-19, it became apparent to even those outside DOD the nature of the problem of the U.S. not manufacturing stateside the critical goods and supplies it needs for its own health and national defense.

"We, therefore, were able to move out and make some investments in industrial capacity and throughput," she said.

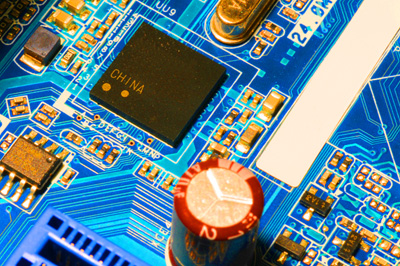

Two areas identified in the 2018 report as being critical are rare earth minerals and microelectronics, both of which she said are necessary for weapon systems and the nation at large.

Lord said the U.S. has some capacity for mining rare earth minerals domestically, as do partner nations Australia and Canada. But for processing of those minerals, she said, the U.S. depends mostly on China.

"We are beginning to re-shore capability for [the] processing of rare earths, as well as working on a strategy to bridge from where we are today with our programs of records and our legacy systems, in terms of microelectronics, until we can get to the future a quantifiable assurance, and knowing what we have in these different chipsets we're buying," she said.

Another issue Lord addressed is "adversarial capital." That's money invested by adversarial nations in U.S.-owned businesses responsible for defense production or other critical products and supplies.

"We use the Council on Foreign Investment in the U.S., CFIUS. DOD is very active in that," she said. "What we are seeing is, unfortunately, nations such as China have taken advantage of the pandemic. They've come in with what we call 'adversarial capital.' And they have bought critical national assets, whether that [is] in terms of intellectual property or whether that [is] technology development or manufacturing."

The DOD, through a variety of methods, has the ability to intervene in such purchases, Lord said. And also important, she said, is to work with allied nations to let them know how the problem of adversarial capital affects both them and the U.S.

"When we work with our partners and allies, that's an even stronger position," she said. "Our adversaries are pretty smart. And they can often go to another country and have shell organizations and so forth. So, when we can partner with other nations to get at that, it's a powerful thing."